Cut, Paste, Repeat

In mid-January, a post from something called Februllage appeared in my Instagram stream. The post was dominated by a calendar of February with a word for each day. Beside the calendar, a small B&W collage of a schoolgirl wearing a hand-drawn crown and hoisting a pair of scissors significantly larger than her head. I clicked onto the post and read further. A clumsy mashup of the words February and collage, Februllage began five years ago when the Edinburgh Collage Collective and the Scandinavian Collage Museum created an open-submission, month-long project. No cost. No entry form. No jury. Simply make a digital or analogue collage every day for the month of February using the calendar of word prompts as a creative springboard. Tag your work with #februllage, and post it onto Instagram. I scanned the word prompt calendar printed in more than a dozen languages and saw concrete nouns, fuzzy emotional states, politically tinged terms and enough ambiguity to create wide pastures of possibility. From this year’s list: bubble, capitalism, escape, encounter, song, plaster, spill, curtain, wrong way. I thought about the shoeboxes of paper scraps I had saved over the years: brochures in foreign languages, vintage medical drawings, maps, flyers and posters from urban life. I’ve been decorating my journals over the years with paint sample strips, ticket stubs and candy wrappers. I am never far from a glue stick. I decided to commit. I imagined crafting collages might bring me a sweet trifecta of satisfaction: play, working with paper, and making art with my hands in a way that evokes the fragrant joy of childhood. What I found during my month of making was that I was not only in with my commitment to produce a collage a day, but I was in a vibrant, active, wildly imaginative global community of collage artists. Kolaj magazine, a Canadian quarterly that “surveys contemporary collage with an international perspective” calls Februllage a 21st manifestation of Surrealists’ parlor games from the 1920s. “If the internet is the house of the 21st century collage movement, then Instagram is its living room. It is the place where artists come together.” The word collage is from the French coller, which means to stick together. Collage is both the process and the product. Though the practice of assembling fragments of paper to make art is believed to have originated in China when paper was first invented there around 200 B.C., the first example of Collage Art with a capital C A appeared in 1912 within Georges Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass, where he glued imitation wood-grained wallpaper into his painting. Shortly thereafter, Pablo Picasso began to add newsprint to his paintings and glued rope around the perimeter of some of his canvases. Those two gave collage cred. Collage traffics in a DIY high/low culture sphere. Paper, cloth, paint, maps, books, matchboxes, found objects, refuse, magazine and newspaper clippings, samplings of other artworks and texts—the list of usable materials is limited only by imagination–are cut or torn, reassembled, and glued onto canvas or paper or any other field to create visually powerful fusions and juxtapositions. The form often has whiffs of political and social commentary, Dadaism, Surrealism, Absurdism and all the other isms that disturb the status quo and subvert the hoity toity patina that art sometimes...

read moreI Can See Clearly Now

Although Buffalo Park was a slip and slide mud festival after last week’s snowfall, I walked a mid-day lap on Sunday. People who had driven up the hill to see the snow clustered around the entry to the park, squealing as they made snowballs and snapped photos. I sloshed alone through the melting snow patches on the Nate Avery trail. About a half hour in, I heard the steady cadence of a runner behind me. He trotted by, buffed and sturdy and splattered with mud. He looked like the human equivalent of a rugged offroad sports utility vehicle in a car commercial. He wore what looked like a heavy backpack, sunglasses, and shorts. His legs were muscular magnificence. He radiated a musky, feral life force. Just ahead was a chin-up bar. The runner detoured off the trail, glided to the bar and tucked into a half dozen pull ups. As I passed by, I watched him exert, heard his labored breath, and marveled at the human body—its beauty, its capabilities—all more acutely compelling in the face of their eventual decay. I was transfixed, as if I were in the presence of something too powerful to fully understand. On my way home I thought about the runner and those feelings. When I told the story later to a friend, she chided me. She heard it as a lament about my aging body. The runner is at his apex; I am in decline. Stop whining, she said, your body still works just fine. But that wasn’t it. Yes, my age was a factor in my swirl of feelings, but it wasn’t the violin section for a pity party. It is my age that gave me the vantage point to take in all the marvel the runner unleashed in me. If my life is a hike, (my analogy of choice) what I know now is that the further along I go, the better the view, the higher I climb, the better the vista. When I watched that runner I wasn’t thinking of my body—my creaky knee, my fading eyesight, my inability to do chin ups any longer–or of his body, really. Instead, I was thinking of all young bodies everywhere and their offhand beauty, the gravitational pull of their physicality, the beguiling and beautiful sight of a human being in top physical form. From my vantage point now as a woman in her sixties, I not only see a bigger picture, I feel a more acute depth to my response. Beauty is everywhere, calling me to witness it. This, I find, is easier from my vantage point. When I was young girl, one of my favorite Olympic sports to watch was high diving. It was only seconds that they twirled and tucked between board and the water, but it mesmerized me. The perfection of their bodies and their movements. The contours of their thigh muscles, the industrial strength of their shoulders. The control and mastery and command. My feelings were never sexualized; instead, it felt to me like watching music and being silenced by my good fortune at beholding something close to perfection. I read a story recently in Forbes about a 46-year-old California billionaire obsessed with reversing his aging process. It has become his life’s work. He has a herd of...

read moreSing With Me

The year after I graduated from high school, I crisscrossed the U.S. in a flotilla of Greyhound buses with about 150 people my age. We were one of three traveling casts of Up With People, a wholesome performance troupe singing across small town America and spreading a message of global goodwill. I wasn’t selected because of my superior pipes or formal training; I was chosen because I could hold a tune and I played well with others. I had sung in my grade school chorus, sung in Sunday church, sung to vinyl my friends and I would spin at slumber parties. But singing in Up With People was next level. We sang as a group for hours every week: in rehearsals, during performances, on the buses. We sang in schools, in prisons and hospitals, on stages, in amphitheaters, in downtown plazas. While I can no longer solidly remember the names of all the cities where we performed, what I can viscerally conjure is the powerful feeling that surged through me when we sang. It was warm, sudden, shimmery and profoundly stirring. I’ve been chasing that feeling ever since–kama muta, a Sanskit word that means moved by love. Researchers at the University of Oslo’s Kama Muta Lab define the emotion as a sudden feeling of oneness, union and belonging. What my year in Up With People taught me is that singing in groups bathes me in kama muta. And the more I feel that good feeling, the more I want to feel that good feeling. When we sing, large parts of our brain buzz and illuminate, says Sarah Wilson, a clinical neuropsychologist at the University of Melbourne in Australia. “There is a singing network in the brain quite broadly distributed,” Wilson says. When we speak, one hemisphere lights up. But when we sing, both sides of the brain light up.“What we are doing when we sing is developing this specialized network, which gives us that physiological reward hit, the chills, the dopamine release, the sense of feeling good,” says Wilson. Singing is ancient, universal and resoundingly primal. There is no human culture on the planet, no matter how remote, that does not sing. Some researchers believe that singing preceded speech. We, as a species, sing for entertainment, for storytelling, to celebrate rites of passage, to beseech our various gods, to recount our victories, to memorialize. Some cultures sing themselves into being. In the belief system of the Aboriginal people of Australia, songlines are the melodic, history-holding paths of the creation ancestors. The origin story goes like this: From what was a vast void, the Dreaming began. Creation ancestors sprang forth and began forming the earth. As they travelled, they created living things and the landscapes that would be their homes. Those travelling paths became songlines of dance and music, song and story that unfurl over generations and carry who they are. Singing in the car, in the shower, as I push a Swiffer over a dusty floor. Singing solo just doesn’t have the emotional oomph as singing in a group. Like some spiritual adhesive, singing in groups binds us, connects us in a form of unity we can’t seem to replicate when we speak with one another. “There is evidence that, in general, singing in a group enhances our empathy and...

read moreMy Lipstick, Myself

It is the 1960s, and I am five. I’m with my mother in our suburban bathroom, watching her apply makeup. I am mesmerized. And I am imprinted. She holds her Maybelline oval cake of eyeliner under the faucet and coaxes a few drops of water, swirls it with a tiny brush, and swooshes it atop her lash line. She dabs at her nose with a powder puff. She darkens her brows with a pencil. And then the ritual de la resistance—the lipstick–always the final, dramatic act. She swivels the lipstick up from its tube, leans into the mirror. She sweeps some frosted orange shade back and forth, rubs her lips together, dabs away some excess at the corners of her mouth with her pinkie. When she’s done, she pulls off a square of toilet paper to blot her lips, leans back, takes it all in, and smiles like a Cheshire cat. I started wearing makeup when I was in high school. Some mascara, some blush, a smidge of eyeshadow usually in a garish blue that was in vogue at the time, but never lipstick. Lipstick was for moms or movie stars. When I was in my late teens and early 20s at university, I embraced the flavor of feminism popular at the time. Scholars call it second wave feminism. Loosely defined, this wave saw the conventional ideas of femininity as incompatible with feminist beliefs. We had serious work to do, rights to fight for. We didn’t have time to apply eyeshadow. Fashion and glamour were considered superficial and diminishing. So, I spent my college years rejecting bras, pantyhose, curlers and girdles—the femininity food groups for my mother’s generation. Giving those up was not a sacrifice because they weren’t my jam anyway. They belonged in the province of old ladies. But I wanted to fit in with my feminist crowd and fight the power, so I didn’t shave my armpits. I cancelled my subscription to Glamour magazine. And I boycotted the cosmetics industrial complex. Sort of. I still wanted to wear makeup. I liked it. The ritual, the transformation. Nothing too much but just enough to get the psychological boost that felt like a sugar high. I liked painting myself, playing with color and contour. But to remain true to my newly found personal politics and the unspoken rules governing that belief system, I wore my cosmetics on the down low and developed what I considered a morally righteous taxonomy: Mascara yes. Blush yes, but sparingly. Eyeshadow no. Lipstick absolutely not. Could I be a feminist and still wear lipstick? I didn’t think so. Some might say that wearing lipstick is a superpower. Coloring the lips has been a practice for at least 5,000 years when Mesopotamian women crushed gemstones and mixed them with beeswax to adorn and color their lips. Reportedly, Cleopatra blended pulverized carmine beetles and ants to create a crimson hue for her lips. Lip color didn’t morph into lipstick until around 1880 when it moved from being kept in tiny pots and applied with fingers to being something akin to a skinny Vienna sausage–a rigid, tubular mass that was congealed with grape seeds. The stick didn’t swivel; instead, it was pushed up out of its tube and locked into place with a mechanism similar to...

read moreBored Certified

This summer I joined a large group of broken people. After a torqued misstep and a hard fall onto a broken sidewalk, I ripped my meniscus and watched my knee swell into what looked like a head of angry cauliflower. Inside, it felt like a batter of hot lava spiked with razor blades. As I awaited orthoscopic surgery in July, I hobbled around the house, ice packed the joint into submission, and felt sorry for myself. I believed I had some valid reasons for my self-pity, but because I had a three-month summer vacation, a backyard full of pine trees that rustle in the summer wind, and loving friends, those poor-me feelings didn’t find sufficient traction. Instead, I moved onto boredom. I am someone who does not get bored easily. Or perhaps I don’t admit it as often as I feel it. We live in a culture that assigns status to busyness. Stimulation is only a scroll or click away. Productivity is the holy grail, and boredom is not a celebrated state in our attention-hijacking economy. I have spent much of my life regarding boredom as a personal failing, much like Dino did, the protagonist of Alberto Moravia’s novel called Boredom. “Boredom to me consists in a kind of insufficiency, or inadequacy, or lack of reality.” That’s how I saw it, too. If my inner life was a multi-plex, couldn’t I just cue up another reel to capture my attention and ferry me into stimulation? Like everyone, I suppose, I can get bored cornered at a party by someone who drones through a story, by a professor bloviating through a lecture, or by an unexpected empty evening colliding with a lack of energy and imagination. Like many, I suspect, I’ve tucked into binging Netflix or pouring another glass of wine as diversionary tactics to combat my occasional bouts of boredom. Boredom has vexed evolutionary psychologists who believe that emotions should evolve for our benefit–not to push us to self-destruction. “The very fact that boredom is a daily experience for many suggests it should be doing something useful,” says Heather Lench at Texas A&M University. Feelings like fear help us avoid danger. What does feeling boredom achieve? First off, boredom does not mean you have nothing to do. “When we’re bored, there are two key things happening in our mind,” says John Eastwood, a psychologist at York University in Canada, and author of Out of My Skull: The Psychology of Boredom. “The first thing is what I would call a desire bind. That’s when someone is kind of stuck because they desperately want to do something but they don’t want to do anything that’s on offer. Secondly, when you’re bored, your mental capacity is lying fallow.” Laying fallow like soil left to rest and regenerate. Contemporary research shows that being in a state of boredom encourages us to create because our brain is signalling that our current situation is lacking. Letting our minds wander is crucial for creativity; we can only attain this state if our mind is idle. Boredom beautifully idles the mind. Even though I felt housebound and irritable, my boredom this summer didn’t feel as if it were a response to being stuck. Eastwood, like other researchers who study boredom, encouraged me to see boredom as a...

read moreOh Say, Can You See?

I used to write occasionally for the Miami Herald, my local daily newspaper. One day some years back I visited the newsroom to make changes to a story I’d submitted. I sat amidst the din, my head bent over a computer keyboard in pronounced concentration. “May I have your attention?” I looked up to see a knot of people. One woman carried a little cake covered with chocolate frosting and crowned with a lit sparkler and a plastic American flag. About three dozen people formed a semi-circle around the desk that held the cake. In the midst of everyone was a young man in pleated trousers, tasseled loafers, and a red, white and blue tie. “My name is Etienne, as you all know, and today is one of the proudest days of my life,” he said in a soft voice, laced with a Caribbean cadence. “Although I was born on the island of Haiti, I had to leave my country because of the troubles. And though my island will always be in my heart, another country is there, as well. Today, I became a citizen of the United States.” Etienne beamed as if he’d just won the lottery. “I am so proud, so thankful. And I would like to sing this song to you.” He cleared his throat, ceremoniously clasped his hands in front of him and began “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Etienne’s voice stumbled a bit as he negotiated the tricky melodic patches. I hummed along, wondering when the last time was that I had sung the national anthem with so much genuine emotion. Ever? “O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave,” his voice rose into a crescendo. Tears leaked from his eyes and fell toward his prideful smile. Silence coated the air before the crowd again broke into applause. A handful of reporters went forward to congratulate him. I returned to my computer to complete my editing. The memory of that afternoon has been flickering in my mind. I’ve spent more than 12 years as an ex-pat, working and living abroad. I view my country’s maneuverings refracted through the eyes of friends and acquaintances from Eastern Europe. Sometimes I am asked to explain our foreign policies, to decode our relationship with guns, to help make sense of political leadership. I cannot. Instead of feeling the strain of pride I saw I Etienne, I’ve spent my adult life questioning, bemoaning and criticizing the United States, a practice whose acceptability is dwindling even though we are a country where challenging the status quo is baked into our national DNA. The summer after I watched Etienne sing the national anthem, I was in the midst of a two-week business trip to a handful of Caribbean islands. Jetlagged and sunburned, I arrived the morning of July 4 on Saba, a rocky, green speck of an island within eyeshot of St. Martin. Saba has fewer than 1500 people living quietly on four square miles of stingy soil. I spent the afternoon with Will Johnson, the local newspaper editor, talking about his minute Dutch island and his 25-year-long, self-appointed mission to produce and distribute the only newspaper his island has ever known. As his wife refilled our coffee cups and served us our second slices of carrot cake, Will and...

read moreThe Tragic Balkan Poet

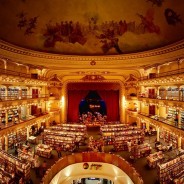

About 20 years ago, I was awarded a Fulbright grant to teach journalism in Tirana, Albania, the capital city of what was then Europe’s poorest country. At that time, Albania lurched and sputtered in its rebranding from a mysterious Communist outpost to a capitalism-fueled democracy. When I arrived there, the country had no ATMs, no constitution and no steady stream of electricity. Classes at the university were held in a three-story Italianate building, painted in a fading rose and mustard color. Two columns flanked a central staircase in the foyer, which always smelled faintly of the hygienically challenged Turkish toilets down the hall. Tucked in the foyer corner was the librari, a bookstore the size of a garden shed with broken, dusty panes of glass and a chunky padlock on the door. There were no closets fattened with supplies, no humming Xerox machines, no glossy catalogues and no textbooks. Entry to the school was by examination or by forking over a hefty bribe. My classroom sat on the third floor, room 305. The students shared desks and wobbled on mismatched chairs. A square of black paint swathed onto the wall served as the blackboard. No eraser. No chalk. Casement windows along one wall provided the only source of light. It’s the first day of class. I’m nervous, but curiosity propels me past fear. Diana, a television reporter who is also my translator, stands beside me. I ask the students to introduce themselves. They wear jeans and backpacks. Their names are dissonant jazz: Etjola, Gjergj, Xhulieta, Zylyftar, Ermal, Manjola. One of my students is Alfred, a young man with a slight scowl, cheekbones like diving platforms and zealously moussed hair. His hands are luminous with long, white fingers. In my mind I nickname him Tragic Balkan Poet. I scan the 29 faces and return to Alfred’s. I am drawn to how pale and haunted he looks. I ask the students to write a paragraph explaining why they want to be journalists. Diana reads their responses later as we sit in Cafe John Belushi and drink warm, foamy Turkish concoctions called salep. Alfred wrote, “I love the horror of being with a white sheet of paper that has to be filled.” Mira wrote, “It is something difficult and things difficult are also beautiful.” Alban wrote, “Suffering is the most important thing in life. I am nothing if I cannot tell my stories.” Perhaps they’re all tragic Balkan poets. I write a comment on Alfred’s paper, complimenting his lyrical prose. “There’s a hint of poetry in your writing, your word play,” I say. After the next class he approaches me. His hands tremble slightly and his eyes dart. In a soft, papery voice he asks Diana to tell me that he is indeed a poet. He says he has published a slim volume of his work. It is entitled, “I Am Born Dead.” The semester unfolds. I announce that every Friday I will park myself from 11 a.m.-3 p.m. at Cafe Pergolah, a small place with outdoor tables near the university. If anyone wants to come by and chat, I will buy the coffee. We’ll be on our own with language, I say. Diana won’t be there to translate. About a dozen students show up on those Fridays. Alfred is always among them. We...

read moreMuch Ado About Nothing

About a decade ago I was invited by Dan, a jazz pianist, to be a participant at an artist’s retreat. I met Dan at a Nevada Arts Council meeting held in the conference room of a swanky Vegas mega-hotel. We were panelists awarding grants to arts organizations around the state. I could hear the faint musical encouragement of casino slot machines as we sat behind name cards discussing the dozens of applications stuffed into lethally sized binders. Cigarette smoke drifted into the room whenever the door opened. Dan told me about the retreat over lunch. He was looking for jazz musicians and poets, he said, because “metaphor and improvisation are two of their food groups.” I was game. In late July, 10 of us met on a dock outside of International Falls, Minnesota and boated to a small island in the boundary waters between the United States and Canada. No agenda, no schedule, no wake-up calls, no Wi-Fi. We spent most of our time solo, canoeing, swimming, staring at clouds and retreating into our cabins to read, write or work on whatever we were working on. In the evenings, we gathered, cooked a communal dinner and sat around a scarred, wooden table sharing the meal and conversation that circled around the idiosyncrasies of creativity. When Dan had invited me, he asked if I would be interested in leading a loose discussion around the dinner table one evening. Any topic, he said. I chose nothing. Nothing. No thing. The opposite of everything. The absence of anything. I wanted to talk about the role of nothing in the things we made. What kind of nothing was something for each of us? I know that talking about nothing can make your brain curly and overheated. It’s like thinking about infinity or what it feels like to be dead. There’s no satisfactory landing pad for your thoughts, and the more you think, the muddier it can become. Philosophers have been duking it out over the concept of nothing for millennia, beginning with the recorded history of the Greeks, who took the stance that nothing was not a viable concept. It isn’t possible, they posited, for nothing to exist. Even metaphysicists, who most often train their pointy-headed hypotheses on what does exist, have ventured into the business of looking at some of the more popular scientific flavors of nothing: omissions, vacuums and void. We weren’t metaphysicists or philosophers. We were a bunch of artists sitting around a table drinking boxed wine, deconstructing what we do. When we spoke of nothing, our conversation tilted toward ideas of rest, pause, space and silence. We talked about the kind of nothing that makes our something, something. The rest between notes. The silence between sounds. The space between words. We turned toward Eastern philosophies where nothingness is cousins with emptiness. Taoist teacher Lao Tsu said, “We shape clay into a pot, but it is the emptiness inside that holds whatever we want.” The Chinese word for emptiness is kong; it is seen as the space between, a fertile place between lives, breaths, musical notes, words. The Japanese have the concept of ma, which is applied to all aspects of life. It is described as an interval, the artistic interpretation of an empty space. It is the vital place...

read moreMy Old Friend Grief

My father’s death in my mid-20s introduced me to grief. The sorrow I felt had a language and texture all its own. So I did what my journalism training taught me to do: drink more and dive into research. I learned about the stages of grieving, the physical symptoms, the scientific blah blah blah of it. Armed with all that information, I felt soothed and masterful, and after a respectable number of months, I thought I’d Marie Kondo-ed my way out of it. The knee-buckling weeping, the dream state numbness, the radioactive sorrow were jettisoned because they did not spark joy. I pushed them into the past tense. Dad was tucked neatly into my memory. I’d made peace. Found closure. Was moving on. Then I ran into a friend in a bookstore. She looked like a crack addict—haggard, glassy-eyed. With my grief-vision goggles, I could see that she had a dust cloud of the stuff billowing around her. She told me her father had died a few weeks earlier, and this was the first time she had left the house. “You lost your father too, didn’t you?” she asked in a trembling voice. Then the world went small, and we stopped talking. We leaned against a table full of books, crying and holding hands. I didn’t even really like her that much, but grief had branded and fused us. Familiar and dreaded feelings resurfaced, and I was again swimming through oatmeal, back in the gluey eddies of grief. I had yet to learn that grief can play a perverse version of Mother May I, sending us back to the starting line for pretending that we are okay or for hurrying it along. Grief really does not like for you to tell it to go faster. Amplifying my grief was my subterranean shame (I should be getting over this faster!), my confusion (Am I a freak?) and my fear (I will never feel good again.) The more I sought to fold and bend grief into soothing shapes like some sort of emotional origami, the more it gormed all over me, the more it roared back. I was a novice then. Loss now is more familiar, as is the grief that is its travelling companion. I have learned that grief has riptides. Grief is bossy. Grief makes me—makes us all—its bitch. And instead of fighting, denying or managing, I have learned to fall to the ground and roll onto my back like a submissive animal. Grief feels these days like a long foreign film with no subtitles: I am not always sure what is going on, but if I roll with it and stay for the entire film, the end eventually comes, and I am left with a lot to think about. The call came last week. A longtime friend has died. We were once lovers, neighbors, buddies. He was my age, and he died doing what he loved. As I heard the news, I blurred into a feeling of gauzy dislocation. Ah, this. This again. I’ll go to my friend’s memorial service and mourn with the others. I imagine I’ll have trouble sleeping and may find myself crying when I speak of him. I’ll consider the terror of the unknown and the satisfaction of a life still unfolding. I’ll reach...

read moreFrom Here to There

It was late morning as I sat in an emptyish Munich airport cafe, bleary from a transatlantic flight. Six hours loomed before my connection to Sofia. I decided to spend the time drinking coffee and feeling sorry for myself. A smartly dressed older man and woman came to the table beside mine and laid down their carry-on bags, coats, water bottles and backpacks. After a brief discussion in what sounded like Danish, the man and the woman began reassembling their belongings. I glanced, but was lasered into Wordle, determined to keep my winning streak going despite the jet lag brain fog. When I looked up a few moments later at what was their table, I saw an empty water bottle, a crumpled napkin and a small leather bag, the kind people use to carry money and passports when they travel. Despite the state-sanctioned suspicion, we are encouraged to brandish with strangers when we are in airports, I picked up the bag and walked into the concourse. The couple was nearby, ogling muffins in a bakery window. I approached the woman, said nothing and handed her the bag. She looked relieved and sheepish. I smiled at her and walked back to my seat at the café. A few moments later the woman approached my table. She had the countenance of a librarian. She thanked me, stepped closer and reached for my hands. As we clasped, she said, “I shall think of you on this day when I travel. I shall think of your kindness.” We held hands for a beat longer. Then she turned and walked away. My eyes teared at how beautiful and necessary and tender it had been to connect in a wilderness of strangers. Aesop, the ancient Greek storyteller, once said, “No act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted.” Aesop’s idea sounds like a primo blurb for a self-help book, but honestly, those small acts of kindness are a bitch to muster. Especially when I travel. Whatever particles of glamour and ease that may have percolated the air travel that I remember from 20 years ago have evaporated. My usual air travel survival strategy is to hate everyone, avoid interaction and endure. I am the surly and silent passenger in 27C with ear plugs burrowed into her skull and an eye mask that says Leave Me Alone. Post-pandemic bad behaviors, FAA glitches, apocalyptic weatherpaloozas, yipping dogs in carry-on bags, price tags on what used to be complimentary onboard services, ample bodies spilling into my seat. I turn inward, cataloguing my petty miseries. I am a rock; I am an island. I am myopic. What I have difficulty seeing is that all the factors that make air travel so fraught are also the factors that are ripe for small acts of kindness and the rippling goodwill they bring. As individual as I’ve been trained to be in my culture, air travel plops me into a churn of humanity, a Petri dish of nearness, a likelihood of unpredictability. It offers conditions ripe for a reminder of ubuntu, a Zulu word that expresses the idea of interconnectivity. South African human rights activist Desmond Tutu said that ubuntu speaks of the very essence of being human. “It is to say that my humanity is caught up, is inextricably...

read moreMy Friend Elmo

It was in the late 1980s when I was indentured at the University of Florida and saw an ad in our campus newspaper looking for marketing managers for some unspecified “family focused” entertainment business. The ad promised the trifecta: travel, independence and big bucks. Even though I was in my senior year, close to the college finish line and anticipated an internship and subsequent job as a newspaper reporter, I had a dodgy relationship with patience and a dramatic familiarity with instant gratification. I was also on the exit ramp of a relationship with a taciturn older man who preferred the company of bees to people. So I peppered my cover letter with adjectives, inflated my resume and was called for an interview. I got the job. At the age of 22 I was hired as one of four marketing managers for the Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers Circus. Yes, I am that cliché: the one who ran away and joined the circus. Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers has folded its tent poles now, but back then it was an old-fashioned circus that travelled by train, paraded its animals through the center of small towns and set up a three-ring venue in a parking lot, using elephants to hoist the red-and-white striped tents. While Ringling filled auditoriums with whiz-bang-glitz pyrotechnics, the Clyde Beatty-Cole Brothers circus hewed to a modest production saturated in nostalgic Americana with sideshows, airborne acrobatics and a fairway that featured a bearded lady!!! And the world’s tallest man!!! My job was to drive into town three weeks before the show. I set up ticket sales, hung posters, schmoozed locals, secured permits and did what I could to froth up the locals. The job had sounded exciting in the ad; it was instead cripplingly lonely. I was in obscure, forlorn towns where I knew no one. During the day, work filled my time, but in the evenings I returned to my cheap motel room, ate dinner from a vending machine and medicated with wine and lethal amounts of network television. For the 10 months I had the job, my only companion was Elmo. Elmo the clown. Elmo was a white-faced clown. He wore a massive, marigold-colored Afro wig and stuck a red Ping Pong ball on his nose. A fat, white crescent moon of an upturned smile outlined in black took up most of his face. A black X crossed the white circles around his eyes, and his painted-on brows were up near his hairline. Baggy overalls covered a blue-and-white checkered shirt that looked like a tablecloth from a shopping mall Italian restaurant. He waddled on puffy, oversized shoes and carried a four-foot-tall yellow foam hammer that he tapped on people’s heads as an exclamation point to his sight gags. About a week before the circus pulled its pomp into town, Elmo arrived in a pickup truck pulling his little bubble of a trailer. Elmo was an advance clown, and his job was to work the town. My job included accompanying Elmo to everything. The first time I met Elmo, he knocked on my motel room door one evening in his full clown gear. “What’s your real name?” I asked. “Just call me Elmo,” he said. Then he hit me on the head with his foam hammer. He was smiling. He...

read moreOptimism is my superpower

Optimism is the faith that leads to achievement. No pessimist ever discovered the secret of the stars, or sailed to an uncharted land, or opened a new doorway for the human spirit. Helen Keller Mad respect to Helen Keller and her starchy endorsement of optimism, but I don’t subscribe to the notion that pessimists have never swashbuckled or furthered the species. I don’t have any hard science on this, but pessimists are everywhere. And we can’t just write them off. They teach university courses. They cut our hair. They friend us on Facebook. They marry and breed. And they outnumber us. Us optimists. “I am an optimist” is not the small talk nugget I am keen to deploy at a networking mixer hoping to impress strangers. Optimists are pegged as naïve, as 24/7 happy-mongers. We are dismissed as lacking the intellectual heft to see the world as it truly is: hopeless, dark, destined for failure. Pessimism skews as fashionable, cool, the POV of the counterculture. Ever stylish, it drapes itself in cynicism. But, pessimism is standstill. Optimism is locomotion. Ample research says that we are all hardwired for optimism; it’s baked into our mainframes. Countervailing research says optimism is learned. In her quote above, Helen Keller calls optimism a form of faith, implying it as a choice, a decision. Others see it as a force. Christopher Peterson calls optimism a constructive power. Peterson is a former psychology professor at the University of Michigan and one of the founders of positive psychology. He published a crystal ball-gazing paper 22 years ago about optimism and its relationship with wellbeing. In his research findings, he calls optimism “a Velcro construct to which everything sticks.” Rather than a form of attitudinal flypaper, I think of my optimism as a lens through which experiences are viewed as invitations rather than laments. “Optimism is seeing problems as challenges that are solvable,” says Hannah Ritchie, a senior researcher at the University of Oxford. She echoes the sentiment of Winston Churchill: “A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.” Ritchie’s focus is on the intersection of human development and environmental sustainability. She views optimism as vital for large-scale problem solving. We need it to make progress, she argues. Instead of cataloguing problems in a reflexive loop, optimists imagine the uncharted terrain of other ways of being, of solutions the imagination may be as yet unable to conjure. Infused with hope and confidence, optimism is my propulsive belief in possibility. I learned it from my mother. But I don’t wear the team T-shirt or go to club meetings. At times it feels as if I am part of a closeted subculture, but the only person keeping that door shut is me. Why am I embarrassed by my optimism? Hesitant to declare it loud and proud? It could be the superficial misconceptions. Maybe it is because I shy away from the trope as an American living in Bulgaria, a country beset by a pessimism that curdles into defeatism. Or perhaps it is the semantic baggage of the word itself. When I feel self-conscious about my optimism or fatigued maintaining it under the barrage of doom spewing, I think about my large-hearted friend Julie who calls herself a possibilitarian. I think about...

read moreGame Theory; I Give You My Wordle

Each morning I ARISE, brush my TEETH, heat some WATER, make some TOAST and THINK about my day. But first I open Wordle, the tasty online word game less than a year old and more addictive than potato chips. In an interview with the BBC earlier this year, game inventor Josh Wardle said his aim was to make Wordle something akin to “a delightful snack.” And so I bite. But briefly. Unlike chips or the mindless overindulgence snack food can induce, Wordle rations itself: One word a day, five letters, five chances. I traffic in language, make my living talking about words, revere Scrabble, parry with friends over vocabulary, thumb through the dictionary for fun. I had a cat named Alphabet. These I offer as my wordplay dorkus maximus bona fides. When Wordle appeared in my social feeds, I was an immediate acolyte. Lots of us were. According to British psychologist Lee Chambers, Wordle activates the language and logic parts of the brain. My brain—and millions of others—lights up over puzzles because they represent a low-stakes challenge. With Wordle, I get to embark on a challenge wearing my pajamas. However frustrating a game might occasionally be, the dopamine reward for playing the puzzle is a small hit of morning bliss. Wordle’s start cute origin story sounds as if it were conjured by the Hallmark network. Wardle, a Brooklyn-based software engineer, created the game in October 2021 without an intent for worldwide distribution. He made it as a present for his sweetie, whom he has called a word game fangirl. They played it and shared it with some friends who shared it with some friends. And on it went until it found me. A month after it was created, about 90 people were playing Wordle. In early January of this year a function was added to the game that allowed an easy sharing of results on social media. Popularity mushroomed. At the start of this year the number of players began at 300,000 and ballooned to over 2 million players a week later. Twitter added to the velocity. When players began tweeting their results, curiosity and interest spiked. Today millions of people play Wordle in 91 languages including Cornish, Kazakh and Klingon. What began as a gift became a hot commodity. In January the New York Times bought Wordle for its game stable at a price the paper reports was in “the low seven figures.” Time magazine named Wardle one of the 100 most influential people of the year. Wardle tweeted his astonishment at the viral popularity (“I’d be lying if I said this hasn’t been a little overwhelming”) and listed some of the effects of playing the game: “from uniting distant family members, to provoking friendly rivalries to supporting medical recoveries.” Wordle as wellness; that’s some game. According to a March 2022 article on Medium that calls itself the authoritative list of the highest form of commercial flattery, Wordle spinoffs number around 100 and include Absurdle (a cranky version of Wordle), Dordle (two words), Trordle (three words), Hardle (billed as more difficult than Wordle), Xordle (two Wordles in one), Sedecordle (16 words), Gordle (for hockey fans) and my favorites: Dawdl (make as many guesses as you want to solve the puzzle) and Sweardle (a “sweary word guessing game”). Were...

read moreAnd there it was; The return of collective effervescence in my classroom

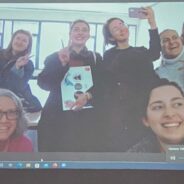

It was about a week ago, a late Thursday afternoon. Outside the classroom windows, golden hour saturated the light with amber. My advanced writing class had just concluded. Seven students Zooming in through laptops vanished from the checkerboard of faces on the projector screen in front of the room. At my university, we are hybrid teaching, a serve-all-customers approach that shortchanges everyone involved. For my advanced writing course about one-third of the students join the class on Zoom; the other two-thirds are there in person. The 15 students who attended in the classroom gathered their backpacks and scrolled through their phones. Chairs scraped the floor as they were tucked under tables. Chatter rose. Students trickled out into the hallway, but about half of them hung back, gathering into a loose circle, goofing in front of the camera that is now a fixture in all of our university classrooms. They seemed giddy. As I collected my things, I watched the students cluster and giggle. And stay. They shot peace signs and teased one another; their delight was sweetly contagious. Palpable. I was drawn to the presence of something being created among them. I’d seen it before in the classroom, but it has been mostly absent since the pandemic arrived. Let’s make a Zoom selfie, one of the students suggested. They beckoned me over. Even though my blood sugar was low, my mood went high. Pinging between us was a stray, spontaneous moment of shared joy, a joy built on the most fundamental of needs: human connection, nearness. I left the classroom and walked home, happy in a way I haven’t been for quite some time. After two years of remote and remove, I had felt once again something vital to my human experience—collective effervescence. In a piece published in The New York Times last summer, organizational psychologist Adam Grant defines the term this way: “Collective effervescence is the synchrony you feel when you slide into rhythm with strangers on a dance floor, colleagues in a brainstorming session, cousins at a religious service or teammates on a soccer field. And during this pandemic, it’s been largely absent from our lives.” During the last two years, like billions of others on the planet, being with others is what I have missed most. I despaired its absence in my personal life, but have felt its tentative return in that arena. I waded, as we all have, through the initial exhaustion and clumsiness of reconnecting. But in the wake of that adjustment, small gatherings, celebrations with friends, dinners out—they are back on my social menu and bringing the connecting satisfactions that they always have. The volume is lower, the gatherings are less frequent, and the groups are smaller, but the peak happiness of sharing an experience with my friends and beloveds is once again part of my spiritual health regime. But that feeling, that possibility, has been more difficult to rekindle in the classroom. There the pandemic remains everpresent and looming. Hybrid teaching does not let me forget how teaching and learning have been denuded. During each class I deejay the technological gear, teach into a camera and talk over the hum of the air purifying machines. I try to yoke together the two learning groups: the students online, a collection of pixels who...

read moreFirst love: Where are you Lawrence Perez?

On a muggy August day before my fifth grade school year was to begin, Mom circled my three brothers, my sister and me. She told us that we were moving to Indiantown, a scratchy, green patch of inland South Florida that we’d visited a few times. Indiantown was all I knew of “the country.” Mom said we’d be moving in a week and living in Indiantown in a trailer on my grandfather’s cattle ranch. It’s just for one school year, she said. She told us that we would move back to our same house on our same street with our same friends in one year. It will be an adventure, she said, which is pretty much how Mom advertised all changes. Mom had told us a couple of times all about Henry David Thoreau and his idea about living a life he made up himself. She said that moving to Indiantown would make us kind of like Thoreau because we too would be marching to a different drummer. Mom said we would be richer because we were trying something new. Money doesn’t make you rich, she said to us over and over again; experiences make you rich. Adventures make you rich. I was 10. I believed everything she said. So we moved to Indiantown. We rode the bus to school and on the days I wore a bra, I sat in the seat in front of Lawrence Perez so he could see through the back of my shirt and maybe notice the wide, white straps. There was nothing yet to notice in the front of my shirt, but I knew from good authority that wearing a bra made your boobs grow. That’s what JoAnn Dwyer told me, and she was one of the only girls in fifth grade whose boobs had budded. Lawrence Perez had oily, black hair and wore the same pants to school every day. He had 11 brothers and sisters. Some of them rode the bus, too, and I heard them behind me speaking Spanish, a language melodic and mysterious. Because Lawrence could speak two languages I thought he was a genius. He sat next to me in class and smiled all the time at everyone, his teeth extra white against his brown skin. During the boring parts of math class he drew pictures of horses in dresses or cows wearing hats. He passed his doodles across the aisle to me when our teacher, Miss Wells, wasn’t looking. Lawrence lived at the turn off onto Fox Brown Road in the migrant worker houses, a cluster of pale blue, concrete houses that all looked like game pieces on a Monopoly board. Mom told us that migrant workers were the people bent over in the fields picking the bell peppers, crook-neck squash, watermelon and tomatoes growing in the farmland all around Indiantown. I saw the migrant workers every morning and afternoon from the school bus window. They wore straw hats and lobbed vegetables into baskets. From the distance they looked like figurines. Near the migrant worker houses sat the Starlite Roller Rink, a corrugated metal building with a neon sign that buzzed and crackled like one of those lights that fries mosquitoes. I didn’t see Lawrence at the rink much, but a bunch of kids from my school...

read moreThe Bins; Goodwill Hunting

Fred went to prowl for vinyl. Audria was a frequent flyer who lasered in on collectible china. Aude and her husband had the eye for mid-century modern in the midst of cheap motel room castoffs. I was fixated on classroom globes from the USSR era. We weren’t a group, but almost every weekend we were regulars at The Bins, the unofficial name of a long gone Goodwill store on Steves Boulevard. The Bins has since migrated to Route 66, and that place has no story for me. But when I moved to Flag in 2005, I made my way to The Bins on Steves to do some thrifting. There I found not just a treasure hunt, but a kooky cosmos that I wholeheartedly joined. The Bins had a recurring cast of oddball characters who orbited there on the weekends and an unrehearsed element of experimental theater. The first time I went, a group of high school boys found a cache of gaudy ball gowns, put them on over their clothes and continued shopping. A woman and her children sported witches hats. Someone was wearing a skirt made out of AstroTurf. Okay, I thought, so this is how we roll in here. I put on a gold lame jacket and a tutu. Kids swarmed, a scratchy radio played KAFF country tunes, and workers rolled dollies of fresh goods in and out of the room with purpose and oomph. The place was an ant farm, a blend of vaudeville, chaos and costume party. And it was like that every time I went. The Bins was a thrift store by definition. It had the usual flotsam and jetsam of discardable contemporary life: obsolete electronics, books of all stripes, dusty textiles, kitchen gear, toys, tools, furniture. But instead of arranged into clusters of similar goods—the standard taxonomy of most thrift stores—The Bins trafficked in surprise, weird juxtaposition and heaping piles of stuff. A mask and snorkel beside a three-ring binder of someone’s vacation slides from Venice on top a Twister game beside a Weed Whacker with bent blades on top of a picture frame adorned with elbow macaroni and glitter. John was the usual Saturday cashier and shop wrangler. He cinched his oversized khakis above his waistline with a wide belt and wore a tattered baseball cap. When he wasn’t weighing and ringing up our purchases, he walked through the store with a beatific smile, as if he were beholding an arcade of wonders. He clucked over the items that had spilled onto the floor, and pinched them back into a bin with his cane-sized grabber. Another Saturday regular was Vampire Guy. He looked to be in his early 20s and wore a black cape with a stand-up collar. He colored a widow’s peak onto his hairline and sported black lipstick. Sometimes he wore horns; sometimes he had a magician’s cane. He stared into the distance as he strolled the aisles imperiously, flicking his cape when he found something interesting. One Saturday as I unearthed a bundle of slips and brassieres that looked like the undergarments my grandmother wore, I heard a faint rendition of “My Way.” An elderly woman, a regular, wore a pink, plastic crown and cradled a cassette tape player that she had plugged into a wall socket. As she held...

read moreGray matters: It’s the color of the year

Longtime L’Oréal face Andie MacDowell showed up on my Facebook feed last week throwing shade on the anti-aging industrial complex. In an interview with The Zoe Report, MacDowell relayed that she was embracing her 63-year-old self by nixing hair coloring and showing her gray. After being cajoled by her children and living through the pandemic curtailment of personal services like haircuts and coloring, MacDowell decided to let her gray flag fly. “I think women are tired of the idea that you can’t get old and be beautiful,” she said. “Men get old and we keep loving them. And I want to be like a man. I want to be beautiful and I don’t want to screw with myself to be beautiful.” One woman’s screwing with herself is another woman’s adornment ritual. MacDowell almost sounds as if she weaponized her hair to brandish it in ideological combat. MacDowell debuted her salt and pepper switch this summer at the Cannes Film Festival. She and others who are professionally beautiful generated frothy copy by walking the red carpet with visible grays. Instead of stories that dove beneath the surface, most of the going gray articles generated from Cannes skewed toward obsequious with distinct whiffs of condescension and sexism: She’s a silver fox! How spunky to go gray! You go gal! In June, The New Yorker ran a photo parade of soft porn hair shots entitled, “Silver Linings.” The images portray women from the realms of the non-famous who decided to let their gray grow in during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of cheerleading through the article, the writer Rebecca Mead questioned the women into examinations of the deeper currents flowing beneath the decision to stop coloring their hair. The women touched on issues of acceptance, transformation, cultural stigma, ageism, social pushback and identity. It’s not just about skipping the monthly marinade of eye-burning chemicals. Going gray means goes deep. According to Statista, a private market and consumer data company, women around the world spent close to $29 billion on hair dye in 2019. Then the pandemic happened. From what I’m reading, hair dye expenditures must have dropped significantly. With the isolation and introspection of lockdown, people slowed and questioned. Significant numbers of women, it seems, decided that gray was OK. We’re all aware (and the advertising industry does not let us forget) that hair has long been regarded for women as a symbol of beauty and femininity, sexual potency and vigor. The Kryptonite for that symbolism has been gray. Gray is an age signifier (even though hair can turn gray at any age) and our hair is a visible message board. It’s not only the melanin that is dwindling, says the gray hair, it is youth. The collateral damage is appeal and power. Maybe we participate in drinking that Kool-Aid. Might coloring our hair actually be ceding power rather than grasping it? Anti-ageism activist Ashton Applewhite posits this counterintuitive idea: “Covering the gray is a way we women collude, en masse, in making ourselves invisible as older women.” In 2014 I was living overseas. I had not yet had the time to suss out a recommendation for a hair salon, but hair coloring is needy habit, demanding monthly hits of time and money. After selecting a random salon for a cut and color,...

read moreFeeding the fire

Photo by Jake Bacon I was a kid at the circus the first time I saw someone eat fire. The circus tent was darkened and a man stood on stage in a circle of light. He wore a sparkly jacket, removed his hat, bent his head back dramatically and used what looked like barbecue skewers to insert balls of fire into his mouth. He closed his lips around each fireball and poof! The fire was gone. It was creepy and thrilling. I also didn’t get it even though I joined in the applause. People eating fire? Why? Doesn’t fire burn you? Aren’t we supposed to be afraid of it? It didn’t win me over, but fire eating has wowed people for thousands of years. As far back as 133 B.C. there is written record of a fire eater named Eunus. Eunus lived in Sicily and, though enslaved, he engendered respect for his reported ability to receive messages from deities while he was asleep and awake. To gin up support for a rebellion that he said was backed by the gods, Eunus made a small fire in a nutshell and tucked the shell into his mouth. He stood before a throng and breathed out smoke, sparks and spikes of fire. It worked. He rallied the troops, freed the slaves and became king. This, however, should not be considered a prudent activity to jumpstart a career as a political activist. Penn Jillette, the vocal half of the American magician duo Penn and Teller, eats fire as part of his job. For my job I have eaten crow, humble pie, my words and my hat. Jillette prefers flames. He described how he taught himself to willingly eat fire at 19 in a 2012 interview with Smithsonian Magazine. “I practiced all afternoon and burned the snot out of my mouth and lips. My mouth looked like wall-to-wall herpes sores, with cartoonish, giant teeth glued to my lips. There were so many blisters I couldn’t press my lips together. I am sure I couldn’t have whistled. I thought I had to ignore the pain and I did.” Why not, instead, ignore the impulse to eat fire? Today, fire eating is associated today with showmanship, street performers and very poor judgement. However, it has a much loftier lineage and was previously used as Hindu, Sadhu and Fakir displays of communing with the divine and proving spiritual elevation. I see the light; I eat the fire. Outside of being eaten, fire itself takes on the heavy mantle of religious symbolism encompassing opposites and extremes — passion, desire, rebirth, resurrection, eternity, destruction, hope, hell and purification. Of the four essential elements outlined by Aristotle, fire is the sole one that can be created by man. In Greek mythology fire was the genesis of man forming civilization. In Hinduism, fire transports, reducing the corporeal form after death to an airborne ash, cleaving the body from the soul to expedite its way toward reincarnation. Zoroastrians believe fire represents God’s light. Other religions deployed less benevolent interpretations and uses for fire. In Christianity, fire symbolized religious martyrdom and punitive zeal. Death by burning or burning at the stake were gruesome public spectacles of punishment for the highest crimes: treason, heresy, apostasy and witchcraft. From religion to literature to folklore to...

read moreDancing with Sir Isaac Newton

A half dozen of us gathered recently for Easter dinner, a collection of single friends. Jazz, rack of lamb, Alsatian wine, animated conversations about politics. It felt like the Before Times. As we tucked into our dessert, the neighbors dropped in—a youngish couple with their 10-year-old son, Andre. About half of the group drifted to the balcony. Andre and I stayed inside, and one of the hosts told him about Zydeco music. Spotify obliged, an effervescence colonized the room, and Andre started dancing on the living room carpet. His open face radiated as he smiled at me. Sir Isaac Newton’s First Law of Motion asserts that a body at rest will remain at rest. It appears that this is especially true for older people at dinner parties. But the latter half of Newton’s law offers the counterbalance to inertia. Law One says that a lack of motion can be broken when it is acted on by an external force. An outgoing child, fizzy music, and an invitation: it was my winning trinity of external force. I joined Andre, and we danced on the carpet, which was checkerboarded with colored squares. Our dancing morphed into a free-style Twister game. We flowed into a stream of play, improvising rules about jumping and freezing in place, daring each other with new moves, squealing in our delight. I didn’t notice when the rest of the grown ups drifted back in. For a good, long spell it was me and Andre and lightness and improv and play and joy. It had been a long time since I felt joy. It had been a long time since I played. The well spoken and wise Belgian psychotherapist Esther Perel says that play is kinetic problem solving. My problem? Overeating from an emotional menu many of us have been tasting since the pandemic descended: ennui, depression, uncertainty, disapointment, stress, burnout, worry. I’m a university professor and like billions across the globe, my work migrated onto a computer screen and my ass found permanent residence in a chair. As David Byrne says: “This is not my beautiful life.” After the initial numbness of the new reality last year, I thawed and knew I couldn’t spend the upcoming academic year lamenting and kvetching. To keep my motor running, I pivoted to a larky, can-do attitude. I attended workshops to explore new ways of engaging students. I adapted. I experimented. Day by day, I put on my teacher face and soldiered into Zoomville, bearing the exhausting weight of pretending and holding space for my students to voice their struggles. I felt nothing; I felt everything. It worked for a while. Until it didn’t. About five friends sent the link to an April 19 article in the New York Times by organizational psychologist Adam Grant who talks about “the emotional long haul” of the pandemic. Languishing is his word for a feeling we may have been feeling but have not properly named. “It wasn’t burnout — we still had energy. It wasn’t depression — we didn’t feel hopeless. We just felt somewhat joyless and aimless. It turns out there’s a name for that: languishing,” Grant writes. I tried on languish for a few days but the fit wasn’t right. Somewhat joyless? Joy had evaporated. Languishers still had energy? I dragged. I...

read moreBoarding Pass

When I was growing up, girls didn’t skateboard. Girls did the dishes. I wasn’t forbidden to skateboard, but it was a boy thing, a thing my brothers did. Back then, breaking into boy territory meant wearing pants to school. We had a long, sloping driveway beside our suburban house in central Florida. After school my brothers busted out the boards and practiced their moves. I watched from the kitchen window—their long, adolescent boy bodies like human linguini as they swirled and stretched into handstands and jumps. I don’t remember envy or longing or a burning desire to join them. But I watched, feeling drifty and mesmerized. Maybe I never wanted to join; I just wanted to watch. These days I mostly move through cities on foot making my way from home to work to shop to park to café. I see the skateboarders hiving on the concrete that covers urban spaces. They cluster and whoop, practice their moves, showing off and veering around walkers, strollers, joggers. They scrape railings, scallop down steps, launch themselves and flip their boards. The cadence of their wheels whirring closer makes its own gritty music. Images of my brothers float to the surface my memory. I didn’t want to join. I just wanted to watch. And...

read moreSofia Audio Dispatch

“I usually associate accordion music with Paris,” the audio story begins, “but I’m not in Paris. I’m in Sofia, Bulgaria… I teach here in Bulgaria, and usually I return to the States for the year-end holidays. But not this year.” Listen to the full audio...

read moreThe Swimming Nuns

When I was about 8 years old, the scariest person I knew was a nun who taught fourth grade at my school: Sister Margaret Joseph. In my dreams Sister Margaret Joseph, or Maggie Joe as we called her, had a recurring, starring role. She mutated into a large bird with barbed wire talons and death-ray eyeballs that swooped down and pulled my hair for crimes like stumbling over a new word as I read aloud in class or asking how the clouds were able to support the cumbersome, ornate throne God reportedly sat on in the heavens above. At St. Francis of Assisi, my Pepto Bismol pink elementary school, Maggie Joe was one of about a dozen nuns who strode the halls, shepherded us to daily Mass, outlined the fundamentals of heaven and hell, and scowled at most of our behavior. The nuns were a stern and joyless lot. We were told they were women, but I could find no proof. I’d never seen legs or hair. They wore no rouge like Mrs. Osborne, the third-grade teacher. They didn’t wear lavender cologne or clip-on earrings like Mrs. McGibney. I could not see their upper arms wiggle when they wrote on the chalkboard like Mrs. Mahoney’s did. And the nuns never praised or hugged me as the lay teachers—and pretty much all the rest of the grown-ups in my life—did from time to time. For the nuns, wooden rulers were the behavior modification tool of choice, and they roundly thwacked our backsides when they said we sassed them. When they scolded us, which was often, they paced menacingly between the aisles of desks. Their folded hands rested on their breast ledges, the only topographical feature in the cascading black robes that began at the neck and trailed to their ankles. Around their necks they wore industrial strength rosaries. Their heads were swathed in elaborate habits. The only patches of visible skin were their faces and their hands. They weren’t all as dour as Maggie Joe. My third-grade teacher, Sister Margaret Anina, had buck teeth and a lisp. She is the one who told us that people with poor penmanship were going to hell. She also spent a lot of time alluding to venereal disease as God’s way of punishing sexual sinners. None of us were that interested. We were fixated on fart cushions and oversize STP stickers we stuck on our three-ring binders. Every day a pack of us in my neighborhood filled the hours until dark playing kick the can. One afternoon my best friend Andrea and I split off from the group to play on our own. It was twilight and time for us to think about heading home for dinner. We hid in the bushes that encircled a neighbor’s swimming pool. We heard voices and saw four women swimming. They wore old lady bathing suits. One of the women sat on the side of the pool and unpinned her hair. Long, grey waves cascaded down her back. As they swam, Andrea and I thrilled at the success of our spying mission. Then one of them stepped out of the pool and put on her glasses. It was Maggie Joe. My face felt hot. I wet my pants. Andrea went to public school, so she did not understand...

read moreThe Things We Carry: Weights and Measures of Living

When I first moved to Flagstaff about 15 years ago, I taught 12th grade English at Northland Prep Academy. The class centered on close reading of a handful of texts. One of my choices was Tim O’Brien’s raw carnival of a book, “The Things They Carried,” a cluster of interlocking stories informed by O’Brien’s service in the Vietnam War. I have a freeze frame memory of the day a student’s face illuminated with an epiphany. Maybe, he said, this book isn’t just about the things that we know the soldiers are carrying—love letters, bug spray, photos—but it is about what they are carrying inside them, their memories, their hopes, their fears. The class hushed as they climbed into the interiors of the characters they had come to know and imagined that dark cargo. That memory bubbled inside me about a week ago as I walked home from work. My energy tank neared empty after a day of hybrid teaching and Zoom meetings. My messenger bag crisscrossed my torso and burrowed into my shoulder. Over my arm, a jacket I would need once darkness swept in. I toted a bag of groceries in each hand. As I made my way through the city center, a radiating weariness befell me. It wasn’t just fatigue; it was a weariness with deeper waters. I stopped to adjust my shoulder strap and dropped all my bags, all my seen burdens. Streetlights had blinked on, and the city center was quiet. I could hear the world breathing, as author Arundhati Roy so beautifully puts it. Why is it that I felt even heavier when I let go? It was as if I could feel all of my life within my body and no amount of rest would restore me to a place of having never known this sensation. My mind drifted back to O’Brien’s book. It wasn’t the things I carried on the outside that gave me pause that evening. It was all I carry with me day in and day out. The loss, the witnessing, the memories of friends and lovers now passed. It was the chapters and costume changes of a long life. As I grow older, I gather more and more into my spiritual folds. My step slows. My burdens grow. I carry sorrow and grief, outrage and disgust. I carry despair. I am in my early ‘60s. As I winnow and Kondo my external life, my internal life grows weightier in an eerie inverse relationship. The tangible possessions I willingly jettison; the stories of aliveness I continue to greedily accumulate. The encounters, the adventures, the gorgeously reassuring ordinariness of day after day. I carry them. We carry them. As I write this, I swerve to a memory, a Roz Chast cartoon in The New Yorker years ago. The cartoon portrays the inside of a head as a finite space, something akin to a dusty basement in a police station where evidence files are stored. As new information comes in—maybe the details about how Kimberly Guilfoyle was let go from Fox News—some older information is jettisoned—maybe the name and biography of a minor Renaissance painter or two? According to Chast and the agitated scrawl of her cartoon, we can only hold so much in our brainpan. Perhaps. But what I know is...

read moreMallard Island/5

This week, something a little different. Laura Kelly recorded this piece for Flagstaff Letter from...

read moreWait for it; Finding the spacious inside the restless

Queueing at the post office yesterday to send a package. Social distancing, masking. I joined the chorus of obliging customers, willing to take our turns. I felt patient and cooperative in my waiting. Video conferencing a week ago with my sibs to discuss our ailing mother. Four there, one late. We small talked and we waited. And then we waited some more. I felt prickly and irritated in my waiting. Digesting the recent dismal numbers showing spikes in COVID-19 infections after all 50 states eased quarantine restrictions. I feel resigned and philosophical in my waiting. How can I get better at it? We can’t go out the way we used to. We can’t be together the way we used to. As much as we want it to be the way we want it to be, reliable data points in another direction. And so we as a nation and me as a person must take this bitter medicine, the prescription that is anathema to our drive-thru, swipe-right, click-here culture. We. Must. Wait. Waiting is a curious, shape shifting enterprise and something that besets us all. We wait in public. We wait in private. We wait alone, and sometimes we wait together. At times we take it on willingly; at other times it is imposed. Vladimir and Estragon waited for Godot. Penelope waited for Odysseus. I am waiting for my UPS delivery guy. We are all waiting for a time when we can dance together, embrace one another and throng in a pageant of humanity, skin to skin. Some of us are perhaps more graceful with waiting. I struggle with it. As a child, I learned that waiting had something to do with not now. Waiting for my birthday, for Santa Claus, for school to end, for dessert to be served. In my childhood religious training, waiting was associated with patience. And patience, I was told, is a virtue. Waiting was inherent in sublimating my timetable for the unforeseen schedule of the Almighty. It felt imposed and unchosen but I was a child believing all that adults told me. As I grew, I moved into other ways of understanding waiting. For the reader in me, waiting is in the taxonomy of suspense. Anticipation builds as my imagination flexes its muscles and sorts through the foreshadowing to see if I am clever enough to predict an outcome or a twist. Waiting has noble elements of discipline, sacrifice and steadfastness. But the most pungent lessons our dominant culture teaches me about waiting are that it is passive and powerless. And worst of all: it is unproductive—a potent, un-American adjective. The contemporary philosopher Dr. Seuss speaks to the thrill of moving outward into the larger world in his book Oh, The Places You’ll Go! The book is a graduation speech staple. In one passage, Seuss relays the pitfalls of The Waiting Place, a way station peopled by lethargic losers: “Waiting for a train to go/ or a bus to come, or a plane to go/ or the mail to come, or the rain to go/ or the phone to ring, or the snow to snow/ or the waiting around for a Yes or No/ or waiting for their hair to grow./ Everyone is just waiting.” Waiting, he admonishes, is not for you. Go getters...

read moreThe crying game; Flying into a vulnerable reality

“Laughing and crying, you know it’s the same release.” —Joni Mitchell I made my way back to the United States last Saturday after the completion of a disorienting spring semester at my university in Bulgaria. The notion of flying internationally unleashed trepidation, but my primal need to be near my ailing mother in Florida was the stronger force. As I walked off the jetway into London’s Heathrow Airport Terminal 2, the vast, empty corridors made my gauges spin. No throngs. No announcements. Nothing. The scene felt confusing and profoundly forlorn. I followed the signs to passport control. As I rounded the corner, I saw the cavernous room cordoned into the maze travelers are usually inching through. I was the only passenger in the room. It was The Truman Show meets The Twilight Zone. I wound my way toward the one open desk and stopped midway. I turned in a slow circle to acclimate to the science fiction. Time and place, near and far, large and small—all of it has been upended. Quarantining at home for two months caged me in the center of a city. Teaching online unhooked me from place. An empty Heathrow Airport liquidated what little was left of the internal architecture I had built to knowingly move through the world. I burst into tears and let them stream down my face. The passport officer was a woman with a halo of curly hair, large brown eyes and sparkly violet eye shadow that extended up to her eyebrows. She softened with sympathy and edited the officialese out of her voice when she asked, “Are you OK?” “I will be,” I said. “But I’ll have to cry my way there.” I cried as she checked my passport. Cried on the airplane that brought me to Miami. Cried when my brother pulled up to the curb to fetch me. Since the pandemic, I have cried watching internet videos of high school choirs, cried when I click “End Meeting” at the finish of my classes. Cried from my Sofia balcony in the evenings when neighbors applaud health care workers. Crying has been my pandemic salve. I have had baklava and potato chips for breakfast, too much wine for dinner, video chats with sympathetic friends and power walks through empty city streets. Nothing feels as spiritually chiropractic as crying. It is a tiny car wash for my emotional traffic jams of the past few months. And it is, as we all know, the dress code for grief. The biggest influence on my life has been my mother, who is an anti-crier. She calls crying sentimental (read: weak). As a child, I learned from her that crying as a response to physical pain was OK; crying as a response to emotional pain was not. Points are earned for bucking up and carrying on. Extra points are earned for not feeling the feelings in the first place. As an adult I have come to see that my mother wasn’t tutoring me about crying per se, but her notion that crying is a signpost of vulnerability, and vulnerability is weakness. As a child I drank that Kool-Aid; as a grown up, I reject this tired, patriarchal definition. I choose instead to subscribe to the ideas of Dr. Brené Brown, a researcher who studies human...

read moreTiny faces; I teach. I learn. I isolate. I yearn.

My brother called last night just as I’d climbed under my covers. We traded stories about emotional numbness and our lapsed personal hygiene. I’ve spent the whole day wearing nothing but my underpants, he said. I countered with the admission that I hadn’t showered in five days. He told me that my nephew—his 25-year-old son living and working in New York City—has a new girlfriend. They’d all shared a Zoom dinner last night. My nephew and his new sweetie cooked pasta in Brooklyn; my brother and sis-in-law cooked pasta in Miami. How is she? I asked. The new girlfriend. I dunno, my brother said. She was a tiny face on a tiny screen. And this, it seems, neatly encapsulates pandemic togetherness. Tiny faces, tiny screens. I teach media writing and storytelling. Before the pandemic, I was an action film. Now, I am a Cubist painting. Like millions of others around the world, I am now a teacher who talks into a machine. I look at a checkerboard of tiny faces and say what it is I have to say. It gives me vertigo as I undergo this disruption of my identity. After class I twitch with feelings of incompleteness and inadequacy. Not in regard to mastering the technology, but for my disrupted participation in the nourishing, physical space of university. In our university we are a small, enmeshed community of learners and thinkers. Students live on campus; it is there that they meet the world and discuss it deeply. Through this, they engage in the messy ongoing process of creating themselves, and so do I. We participate in what Professor Gert Biesta calls “the beautiful risk of education.” It’s a Monday, and I have class at 4 p.m. I sit in my kitchen wearing yoga pants. I’m barefoot. Half a sandwich sits in my lap. I talk into a silver portal and speak to my own face. Inside my head I am distracted by the places where my hair sticks out and self-conscious about my propensity to gesture like an opera diva even, it seems, when I am the only person in the room. Is there learning happening online? Almost certainly, but I have not yet recalibrated my meters. Mostly classes feel like being together in the dark. The public chat space is where my students want to communicate but for discussion we need to talk out loud. They unmute their mics and their voices come from nowhere, startling me with their potency. I don’t want their tiny faces; I need the intimacy of their disembodied voices for any of what I am doing to make sense. I find some comfort knowing I am one of millions of teachers unfastened from the familiar architecture of our daily lives and rewriting ourselves as educators. I’ve been reflecting deeply on what my work means. What I mean to the work. I read about the Maori word ako, a concept that does not ask for the teacher to know everything. Instead the value is put on reciprocal relationships. Teachers create settings where everyone brings knowledge with them and shares it like a big potluck dinner. I read more from Biesta, a theorist and professor who is measured and philosophical in his approach to education. He calls it a practice, a slow practice...

read moreEating cake in the bed; On the pleasures of being an aunt